Hidden Losses

Australia’s Overlooked Marine Species at Risk

Diving into Decades of Change

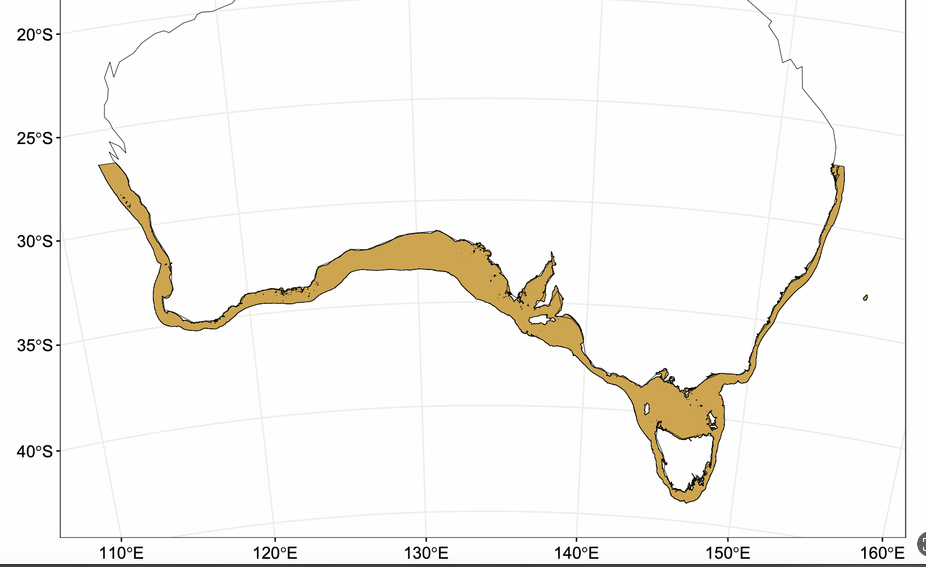

Australian marine ecosystems, including the vast life-rich Great Southern Reef, are renowned for their diversity. Yet many species critical to these environments remain significantly undervalued — and understudied, largely due to persistent gaps in monitoring and conservation assessments.

A new study led by Olivia Johnson from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) highlights the scale of the problem. Drawing on one of the world’s most comprehensive reef biodiversity datasets, the researchers examined records for more than 3,400 marine species. But only 626 had enough data to assess long-term trends — just 18% of the total. Among 108 seaweed species analysed, not a single one had been formally evaluated for extinction risk by the IUCN Red List.

Image: Reef Life Survey (RLS) Diver in Albany by Olivia Johnson

Diving into Decades of Change

The study synthesised decades of survey data from the Reef Life Survey and Australian Temperate Reef Collaboration programs. Divers conducted standardised underwater visual censuses along more than 2,600 transects around Australia’s coastline, recording species density, cover, and presence across fishes, mobile invertebrates, seaweeds, and corals .

Foxfish by Olivia JohnsonOnly species surveyed at 30+ sites and across at least four years were analysed for population trends — a rigorous standard that reinforces how many species remain invisible in long-term conservation planning.

Under the Radar Seaweeds

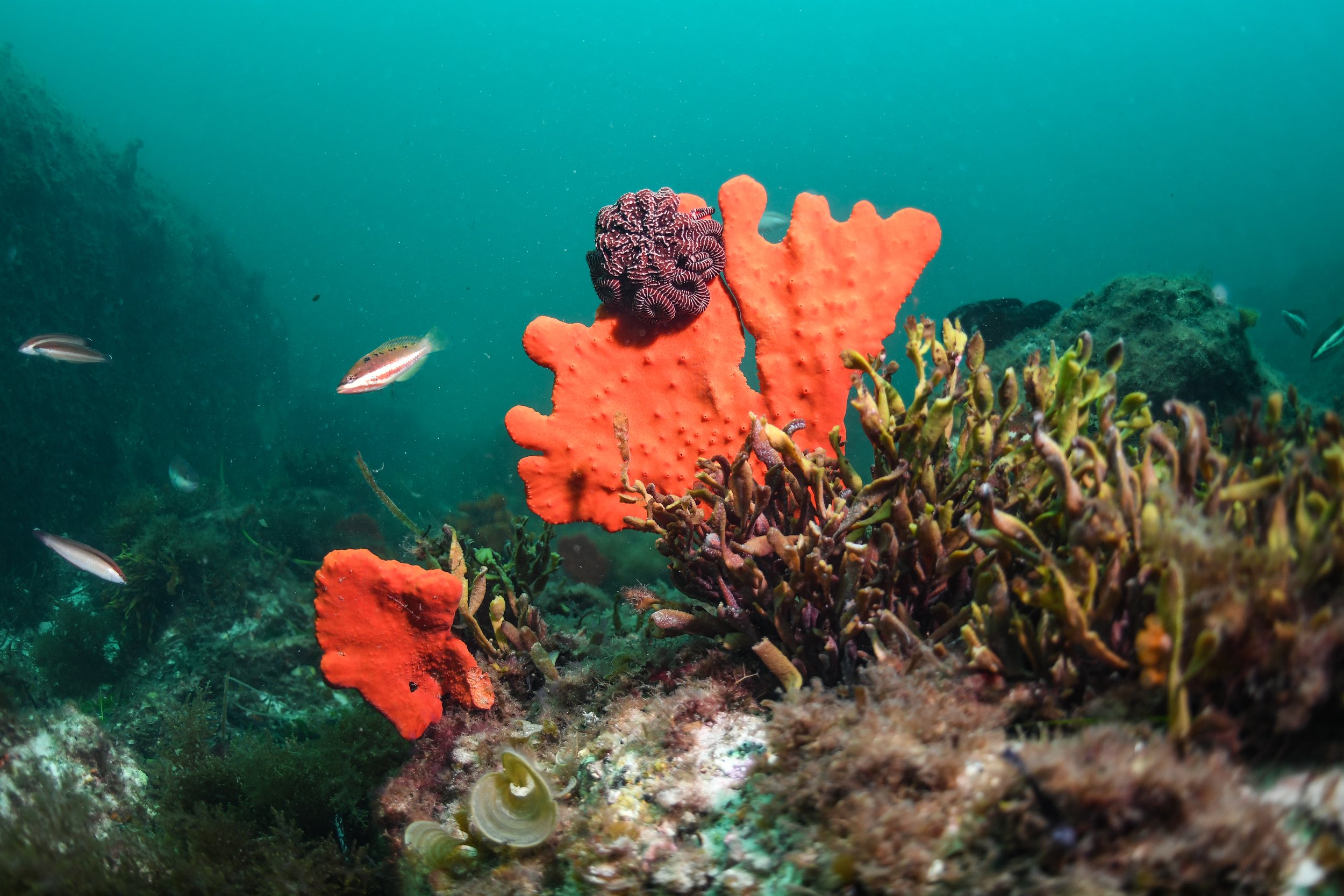

Large habitat-forming seaweeds, such as kelps and fucoids, play a foundational role in reef ecosystems. Yet they’ve often been sidelined in conservation because they’re less charismatic than large marine animals — and because we lack consistent, long-term data.

“Large habitat-forming seaweeds are fundamentally important,” Johnson explains. “They provide structure, food, and shelter for countless marine species. Unfortunately, they're often overlooked... because we simply don’t have sufficient data.”

Image: A reef near Albany, WA by Olivia JohnsonBull Kelp on the Brink

Among the species analysed, Durvillaea potatorum (bull kelp) stands out. Found along southern Australia’s cooler coastlines, its dense canopies shelter a wide range of species — including commercially important fish and shellfish.

However, populations of bull kelp have suffered dramatic declines — Olivia Johnson’s paper notes a staggering 66.6% loss over the past three decades and almost 30% in the last decade. Warming waters, extreme storms, and habitat disruption are among the key drivers.

Image: Bull Kelp in Tasmania by Stefan AndrewsBeyond their ecological role, bull kelp holds deep cultural and economic significance. Indigenous communities along southern Australia's coast have used bull kelp for thousands of years, crafting water carriers and ceremonial objects. Commercially, bull kelp once supported an industry contributing around A$2.5 million annually to global alginate production.

“Bull kelp is particularly vulnerable to ocean warming,” Johnson explains. “It requires cold, nutrient-rich waters to thrive. As the ocean continues to warm, we’re seeing declines that impact marine biodiversity, cultural practices, and fisheries alike.”

Canopy-forming Seaweeds suffer

Another significant canopy-forming seaweed highlighted by Johnson is Scytothalia dorycarpa, a warm-temperate fucoid species found across southern Australia. Scytothalia suffered major declines following Western Australia’s 2011 marine heatwave, with Johnson’s analysis showing it has experienced one of the steepest decadal declines among all seaweeds assessed in the study — 77% per decade.

Image: Lessonia in Tasmania by Hunter ForbesThe Tasmanian endemic Lessonia corrugata (strap weed) is another species of serious concern. A dominant canopy-forming kelp on southeast Australian reefs, it declined by 49% per decade — placing it just below the threshold for Endangered status under IUCN criteria. This species has a thermal tolerance of only 22–23 °C, and with ocean warming accelerating, it may exceed these limits as early as 2050. Loss of L. corrugata could also result in the disappearance of many associated species — with previous studies in Tasmania suggesting that as many as 150 taxa rely on these canopy forming species for habitat structure.

Overlooked Marine InvertebrateS

Marine invertebrates — from sea cucumbers and starfish to molluscs — are the unsung majority of ocean life, representing around 98% of marine animal species. These organisms are vital to the health of reef systems, playing key roles in nutrient cycling, water filtration, and maintaining ecosystem balance.

Yet despite their ecological importance, invertebrates remain largely absent from conservation conversations. Olivia Johnson and her co-authors found that the vast majority of common shallow-reef invertebrates assessed in the study — around 80% — had never been evaluated for extinction risk by the IUCN Red List.

Image: Basket Star in Western Australia by Scott Bennett“Marine invertebrates typically lack sufficient data for effective conservation assessments,” Johnson explains. “This has significant implications for overall marine biodiversity. We urgently need more investment in understanding and protecting these species.”

The issue reflects broader trends in global conservation. As of 2021, marine species accounted for just 11% of all listings on the IUCN Red List, while terrestrial species made up 58%. Without consistent monitoring and taxonomic attention, many marine invertebrates risk declining unnoticed — silently eroding the foundations of reef ecosystems.

Image: Short-Spined Urchin (Heliocidaris erythrogramma) and Pencil Urchin (Goniocidaris impressa) by Olivia Johnson. Both endemic to southern Australia, are among invertebrate species found to be in significant decline.The Forgotten Fishes of the Southwest

The study also draws attention to concerning population declines among several reef fish species in southwestern Australia. Five species stood out for their significant decadal declines: the false senator wrasse (Pictilabrus viridis), wrasse (Dotalabrus alleni), yellowhead hulafish (Trachinops noarlungae), banded sweep (Scorpis georgiana), and McCulloch's scalyfin (Parma mccullochi).

Image: Banded Sweep in WA by Scott BennettThese species, many of which are endemic to temperate Australia, face increasing pressure from warming waters and habitat changes. Several were strongly affected by the 2011 marine heatwave that caused major ecological shifts across Western Australia’s reefs. Despite evidence of decline, most remain poorly represented in conservation planning, and several have outdated or missing IUCN assessments — limiting opportunities for timely intervention.

These southwestern fish species face pressures likely linked to warming waters and regional habitat shifts. Some declines may also relate to limited monitoring coverage, particularly in more remote reef systems. “The southwest marine region hosts species with highly restricted distributions,” Johnson notes, “and many are experiencing population declines in areas that may be under-monitored or lacking targeted conservation action.

Rethinking Conservation Standards

Johnson’s findings highlight broader limitations in how current global frameworks assess extinction risk, particularly for marine species. While the IUCN Red List remains a critical tool for conservation planning, its criteria were originally developed with terrestrial vertebrates in mind — making it difficult to apply effectively to marine taxa such as seaweeds and invertebrates.

This imbalance is evident in Johnson’s data: of the 401 fish species assessed in the study, 84% had existing IUCN Red List assessments — whether current or outdated. In stark contrast, none of the 108 seaweed species analysed had ever been assessed, underscoring the taxonomic bias that continues to shape conservation priorities.

A nudibranch, Stylocheilus striatus on kelp and sacoglossan sea slug, Elysia maoria by Olivia Johnson. Gaps in conservation status

Many marine species — including those critical to reef structure and function — lack the detailed life-history data or broad geographical records needed for full IUCN Red List assessments. This leaves significant gaps in our understanding of marine biodiversity, with many ecologically important species either classified as “Data Deficient” or not evaluated at all.

Johnson noted that many provisionally threatened species remain listed as "Least Concern," and over half of the Red List assessments in their dataset were more than a decade out of date.

“It was surprising to see how many assessments were either missing or out of date,” she says. “In a rapidly changing environment, especially with accelerating marine heatwaves and habitat loss, a lot can change in ten years — and outdated assessments risk masking serious declines.”

Weedfish by Olivia JohnsonAs Johnson points out, conservation action is often closely tied to official status. Without accurate and current assessments, species may not receive the attention or funding they need — regardless of how vulnerable they actually are.

As Johnson’s work highlights, without tailored assessment approaches that accommodate the realities of marine ecosystems, conservation efforts risk systematically overlooking the species most vulnerable to decline. This broader issue has been the subject of recent work by Johnson’s PhD supervisor and co-author, Graham Edgar.

Navigating Data Challenges: Insights from Edgar’s New Work

Providing essential context to these findings is Graham Edgar, Olivia Johnson’s PhD supervisor and co-author of the study. Edgar’s recent work, IUCN Red List criteria fail to recognise most threatened and extinct species, identifies deep-rooted flaws in how global conservation frameworks assess extinction risk — particularly for invertebrates and seaweeds.

Drawing from extensive experience with over 200 Red List assessments, Edgar argues that the current IUCN criteria are fundamentally skewed toward large, terrestrial vertebrates. For inconspicuous marine taxa, particularly those with small ranges or cryptic life histories, the criteria often produce inconsistent, or even misleading, threat categories. Critically, species undergoing severe declines may be relegated to “Data Deficient” simply because their populations fall below detection thresholds — not because they’re safe.

Red velvetfish by Olivia Johnson. Despite showing long-term population decline, it remains unlisted by the IUCN Red List.“Invertebrates and habitat-forming seaweeds rarely receive the attention they need,” Edgar writes, “because they lack the data required by outdated assessment frameworks. But without that recognition, conservation efforts stall — we can’t protect what we don’t see.”

Johnson reflects on this collaboration: “Graham’s work helped illuminate how systemic bias plays out across marine conservation. His insights pushed us to think more critically about not just the data we have — but the data we’re missing, and what that means for species already slipping through the cracks.”

Future Directions

Johnson’s work sends a clear and urgent message: conservation efforts must move beyond a narrow focus on charismatic or commercially valuable species. Without robust, long-term ecological monitoring, many critical species — from kelp forests to overlooked invertebrates — will continue to decline unnoticed, eroding the very foundations of marine ecosystems.

"We need to significantly expand ecological monitoring," Johnson stresses. "Without better baseline data, many species will continue to decline unnoticed."

A Reef Life Survey (RLS) diver conducting a survey in Tasmania by Scott BennettThe findings call for a fundamental shift: greater investment in population monitoring, more flexible and inclusive conservation frameworks, and a strategic focus on habitat-forming and functionally important species. Only by addressing these persistent data gaps can we close the data gap in our ecological knowledge that leaves vital parts of marine ecosystems vulnerable to silent collapse.

For the Great Southern Reef, one of the most biodiverse and ecologically significant temperate reef systems on Earth, the stakes could not be higher. Proactive, evidence-based conservation is no longer optional; it is essential to preserve the extraordinary life, cultures, and economies that depend on it.

you may also like: