restoration

Australian researchers are working at the global forefront of marine habitat restoration, with projects underway in every state along the Great Southern Reef. Habitat restoration is a resource intensive exercise used as a last resort for areas where vital habitats have been lost or are in decline and natural recovery is not occurring. Currently there are active restoration projects on the GSR working to restore seaweeds, seagrasses, and oyster reefs.

Restoring Marine Ecosystems

golden kelp

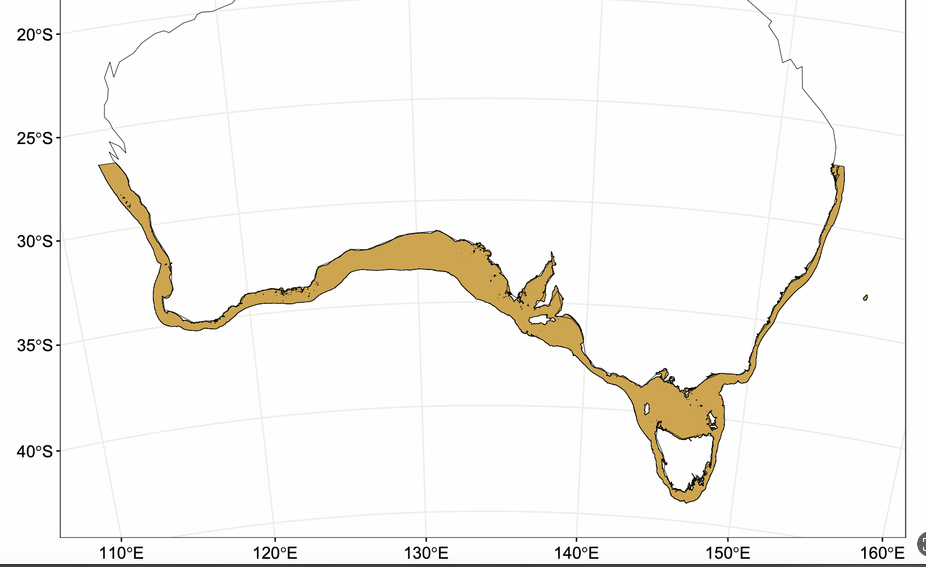

Golden kelp (Ecklonia radiata), forms the backbone of the Great Southern Reef and is distributed throughout the entire 8,000km range of this interconnected temperate reef system.

However, in Victoria's Port Phillip Bay, the ecosystem has been under siege. Sea urchins, flourishing due to an imbalance in the food chain, have overgrazed 60 percent of the reefs, decimating the once widespread kelp and seaweed habitat.

This ecological crisis can be traced back to the 1980s when excess nutrients from wastewater treatment plants led to a surge in weedy seaweed, a primary food source for purple sea urchins. During the millennium drought, fewer nutrients entered the bay and seaweed growth reduced, so the urchins began eating kelp and seaweed growing on the reefs.

port phillip bay Golden Kelp restoration project

Scientists at the Queenscliff Marine Science Centre have been growing juvenile Golden Kelp in the lab on twine and gravel, ready for replanting in targeted areas. The researchers have grown over 6 million juvenile spores onto twine or embedded in gravel pellets. These trials aim to research and develop the most effective methods for golden kelp cultivation and restoration in the bay, setting the stage for future large-scale efforts.

A key component of the project involves managing the overabundant Purple Urchin populations that have contributed to the creation of barren rocky reefs, devoid of kelp. By reducing urchin numbers to sustainable levels, the team is working to restore balance in the ecosystem, allowing kelp and other seaweeds to recover and thrive once again.

This collaboration involves The Nature Conservancy, the University of Melbourne, Deakin University, and Parks Victoria, and is supported by the Victorian Government.

golden kelp seedBank

In addition to cultivating kelp, researchers are establishing Victoria's first Golden Kelp seedbank at Deakin's Queenscliff Marine Science Centre. This seedbank will preserve the genetic diversity of Golden Kelp, ensuring its resilience and long-term conservation. Collected from various locations around Port Phillip Bay, reproductive material will provide crucial resources for future restoration efforts, and the seedbank is being expanded to include sites along Victoria’s coastline.

Green Gravel

Green Gravel, a concept that integrates restoration ecology with the natural process of seaweed reproduction, offers an impressive potential for the restoration of kelp forests on a large scale. The method is simple yet ingenious: marine substrates or 'gravel' are seeded with juvenile seaweeds, which are then scattered across degraded marine habitats.

As GSRF science committee member Melinda Coleman explains, "The green gravel technique harnesses the microscopic life stage of kelp, which is very easy to manipulate and grow in the lab onto small rocks or gravel." This technique, beyond its simplicity, provides an opportunity for customisation and scalability in marine restoration efforts. Scientists can rapidly seed any kelp genotype onto these rocks, enabling them to populate both degraded and existing kelp communities efficiently.

In the face of rapid environmental changes and the alarming impacts of climate change, marine conservation must transition from a reactive to a proactive approach. We must anticipate future ocean conditions rather than only managing for today's conditions, and Green Gravel facilitates this forward-thinking approach. This innovative and versatile technique broadens the potential for large-scale marine restoration, making it more accessible to a broader range of community members and the public.

By employing green gravel, we can explore the potential for "future-proofing" our marine habitats. This involves boosting the thermal resilience of seaweed populations, particularly vital for sessile organisms that cannot move in response to changing conditions. As such, the technique allows for the selection and seeding of thermally tolerant kelp genotypes, which can better withstand the warmer temperatures anticipated with climate change.

giant kelp

Giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) is an iconic canopy forming seaweed that can grow over 35 metres long and up to half a metre each day. Scientists estimate that giant kelp forests have declined over 95% in Tasmania since the 1940′s. In 2012, giant kelp forests became the first marine community to be listed as a threatened ecological community under the Australian Federal Government Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

The main culprit for giant kelp loss is the combination of high temperatures and low nutrients. Giant kelp is highly sensitive to temperature changes and requires lots of nutrients to sustain its rapid growth, particularly under warm conditions. During warm summers giant kelp becomes physiologically impaired, making it more susceptible to diseases and mortality.

Climate change has exacerbated this challenge, transforming the oceanic conditions around Tasmania. The East Australian Current (EAC) is a warm water, nutrient poor current. The EAC is flowing further south than it did previously, displacing much of the cool nutrient rich water typical of the East coast of Tasmania. These changes are largely due to climate change. This warm, nutrient poor water is causing the giant kelp forests to suffer.

Yet, there's hope on the horizon. Scientists are now focusing on resilience as a key factor in the restoration of these kelp forests. By collecting kelp spores from remaining wild populations, scientists are able to culture and store huge quantities of kelp babies in the laboratory that can then be transplanted back onto the reef to restore and rebuild giant kelp forests, from where they have been lost. This innovative approach offers a promising avenue for the future of Tasmania's giant kelp forests in a rapidly changing climate.

other restoration projects:

you may also like: