Sea Country leaders unite

in historic alliance at NSW Parliament

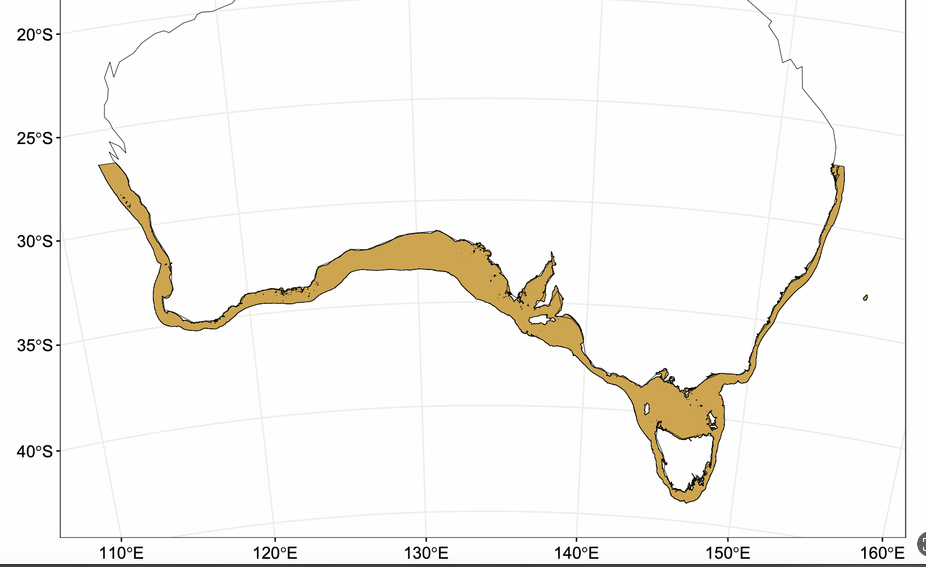

Aboriginal Sea Country leaders, scientists, and industry representatives gathered at NSW Parliament House for a special screening of White Rock - a documentary exposing the explosion of long-spined sea urchins, the loss of kelp forests, and the growing ecological and cultural crisis along the Great Southern Reef.

The event followed a historic meeting earlier in the day where Aboriginal Saltwater peoples from across New South Wales voted unanimously to form a new Aboriginal Sea Country Alliance. The alliance unites coastal Nations to lead the response to the state’s declining reef systems and the erosion of cultural practices tied to them.

Their statement, read in Parliament before the screening, called on governments to recognise Aboriginal connections to Sea Country and to resource Aboriginal participation in reef restoration, marine management and self-determined livelihoods. It was the first time such a unified call had been made at state level, marking a shift from consultation to leadership.

Sea Country in crisis

Once-vibrant kelp forests that sustained fisheries, communities and culture have been stripped to white rock by the overgrazing of long-spined sea urchins, whose populations have exploded with warming seas and the decline of natural predators. The result is a visible transformation along the coast: rocky reefs once dense with life now lie barren.

Dr Jodi Edwards (University of Wollongong), a coastal educator and researcher, gave a heartfelt account of the loss.

Her poetic statement, read after the film screening, captured the depth of feeling shared by everyone present. “These barrens are not just environmental scars; they are cultural wounds... The sea has spoken. The question is, will you answer?”

That sentiment framed the discussion that followed. Speaker after speaker emphasised that Aboriginal communities already hold the knowledge, science partnerships and trained workforce to start large-scale restoration. What is missing, they said, is the political will to activate it.

A call to act, not consult

Walbunja Elder Uncle Wally Stewart, featured in White Rock and a leading advocate for cultural fishing rights, outlined the scale of change along the South Coast. “Half our reefs along 450 kilometres of coastline are barren now,” he said. “We’ve identified the problem. We’ve built the plan. All that’s left is to get started.”

He spoke of frustration at seeing opportunities lost while governments debate process. “Our people have managed these waters forever. We want to keep doing that work. Not talk about it, do it. Give us the resources and we’ll bring the kelp back.”

Marine ecologist Dr Cayne Layton explained that the Western ecological science reinforces what Aboriginal communities have long observed. “These native urchins have become hyper-abundant. They graze reefs to the rock,” he said. “You lose the trees, you lose the habitat, you lose everything else that depends on it. Western science is only now catching up to knowledge that’s been held here for thousands of generations.”

Industry and community ready to lead

Panel Members Cayne Layton (UTAS), Jo Lane (Sea Health Products), Wally Stewart (Walbunja Elder) and Tillmann Bohme (University of Wollongong). Image: Michael PowerIndustry voices also pointed to the clear economic opportunity in restoration. Jo Lane, owner of Sea Health Products, recalled how her business once relied on kelp washed up naturally on beaches along the South Coast. “Those wash-ups started to decline sharply,” she said. “That’s when we realised how serious the problem was.” She has since built New South Wales’ first seaweed-specific hatchery to produce kelp seed for restoration and farming. “The infrastructure is here, the science is here, and the people are ready.”

Tillmann Böhme, (University of Wollongong) business developer who has worked with Joonga Land and Water Aboriginal Corporation, echoed the urgency. “We have trained divers ready to go tomorrow if funding lands. We’ve already built partnerships with industry that want to do this properly. The balance can be restored if we activate now”.

Across the discussion, the message was consistent: the components exist. Trained Aboriginal dive teams, hatcheries, processing facilities and a shared plan. What’s needed now is coordination and investment.

The plan and the ask

The alliance outlined a practical three-part investment plan for New South Wales:

-

$3 million for three ecosystem restoration trials to restore kelp and control urchins.

-

$5 million per year to expand the NSW Sea Ranger Programme, employing divers, deckhands, and marine rangers across the coast.

-

$15 million to develop three regional enterprises in aquaculture, kelp farming, and restoration services.

The plan is scalable, ready to implement, and aligns directly with the Closing the Gap framework and the NSW Marine Estate Management Strategy.

The alliance also reaffirmed support for the $55 million Federal program recommended by the 2023 Senate Inquiry into the management of the long-spined sea urchin. That inquiry urged the Commonwealth to establish a dedicated Centro Task Force to coordinate urchin control and Great Southern Reef restoration nationally. Despite its clear recommendations, the Federal Government has not yet responded and the proposal remains unfunded.

Together, the NSW and federal plans offer a coordinated roadmap for restoration and for Aboriginal leadership in marine management - one that could deliver immediate environmental, cultural, and economic benefits if acted on.

Support for the alliance’s approach was voiced across political lines at the event. Sue Higginson MLC acknowledged the importance of empowering Aboriginal communities “who hold both the knowledge and the solutions”. Michael Holland MP, representing the South Coast for the NSW Labor Government, said he was “personally committed” to progressing the alliance’s proposals through the next state budget process.

Cross-party voices and cautious optimism

Sue Higginson MLC and Michael Holland MP both showed support for the alliance at the event. Images: Michael PowerThe Next Generation of Sea Country Stewards

Custodian of Walbunja Jared Huskin gearing up for a diveThroughout the evening, there was agreement that bureaucratic inertia, not lack of capacity, remains the main barrier to progress.

Beyond policy, the discussion turned to cultural renewal and the next generation. Young Aboriginal divers like those featured in White Rock, represent the future of Sea Country stewardship. They’ve completed maritime and dive training through community-run programs but remain without stable employment while funding decisions stall.

“Our young people are trained, ready and proud to work on Country,” one South Coast woman said. “They just need the door to open.” Another added simply: “Stop paying consultants to ask what’s wrong. Pay the people who can fix it.”

The film screening event closed with a collective statement “We call on the NSW Government to recognise the crisis in Sea Country, fund urchin removal and kelp restoration, and support an Indigenous Sea Country Partnership to lead long-term repair. Immediate leadership from the NSW Government is needed to acknowledge the crisis in Sea Country, resource restoration, and empower First Nations to guide recovery.”

As the crowd filed out, there was little doubt about the message. This crisis is no longer hidden beneath the surface. The people most connected to the coast are ready to lead. The Sea Country Alliance now stands as a unified voice for NSW Aboriginal coastal communities, offering both cultural leadership and technical expertise. It asks for partnership, not charity, for governments to trust those who have managed these waters for tens of thousands of years.

The night did not end in applause, but in quiet determination. Among the final words to echo through the room were those of White Rock’s narrator, Damon Gameau: “This is a no-brainer.”

you may also like: