South Australia’s harmful Algal Bloom

What We Know, What We’re Learning

What’s Blooming Along the SA Coast?

There is a major harmful algal bloom (HAB) in the South Australian marine environment, at a scale not previously experienced. The dinoflagellate species Karenia mikimotoi was the first harmful species to be detected, but there are now other, related and less common species being found in bloom water samples.

An unusual feature of Karenia blooms is their longevity (weeks to months), large spatial extent (they can move many kilometres), and their presence over a large depth range. Karenia bloom cells can move vertically up and down the water column, gathering nutrients for growth in the process.

Header Image: Lochie CameronKarenia is a genus that consists of unicellular, photosynthetic, planktonic organisms. Image Vince Lovko, Mote Marine LabTracking the Bloom: When and Where It Hit

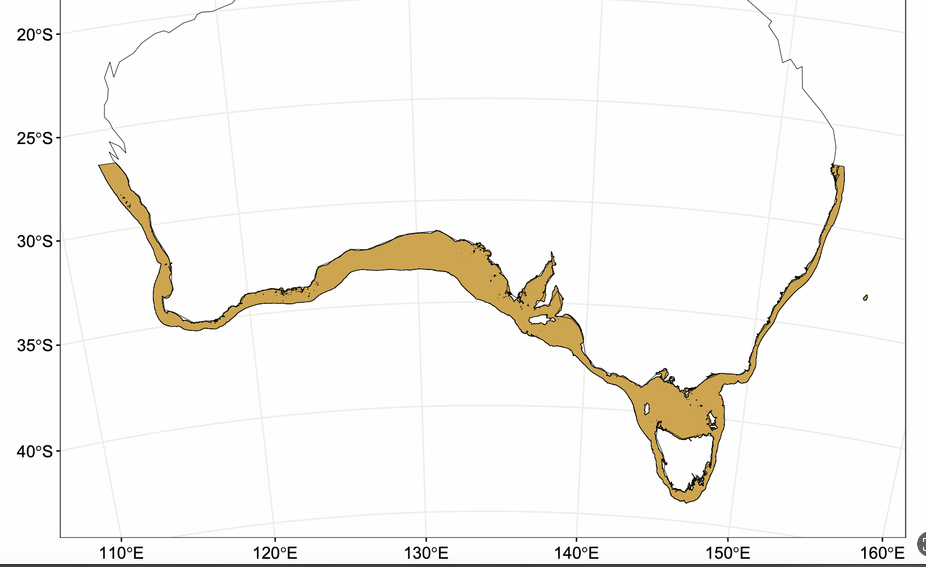

The blooms have expanded with prevailing autumn oceanographic conditions in north-westwards, northerly and westerly directions since at least March. This major HAB has had sustained impacts in some areas, such as the south-east of SA, southern Fleurieu, Kangaroo Island and southern Yorke Peninsula. In late April and early May, the bloom moved further up the western side of Gulf St Vincent.

Chlorophyll-a concentration and ocean surface currents on 26th March, 9th April, 9 May and 13th May 2025 across South Australia, derived from satellite remote sensing and HF radar data. Data and imagery sourced from the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS), accessed via OceanCurrent.It is possible that smaller, separate “mini-blooms” are forming in some areas. Blooms are now also present in parts of Spencer Gulf and Eyre Peninsula. Different toxic algae (not the oceanic Karenia) have been recorded in some of the shallow bays and other nearshore waters, which has closed oyster-growing areas in some parts of SA. Agencies are using the IMOS system’s oceanographic forecasting tools and regular observations to model the path of the bloom, and water samples are being taken frequently.

MORTALITY HOTSPOTS

The figures above from satellite imagery portal IMOS show false colour satellite imagery of chlorophyll concentrations in deeper water areas of South Australia in April and May.

Over the past couple of months, the mortalities being recorded in SA have matched the distribution of oceanic chlorophyll content in bloom-impacted areas.

(Note that the “red zones” in very shallow bays and at tops of the gulfs on these dates are not indicative of the oceanic bloom, as sediments and multiple species of common microalgae in shallow bays, can have the same reflectance values in remote sensing).

Some of the early reported warning signs of the HAB were dead fish floating on the ocean surface several miles offshore from Cape Jaffa in March. Fish deaths were also being recorded in the lower south-east even earlier, in late summer.

SYMPTOMS from A SICK SEA

Foam at Knights Beach, Port Elliot in late April by Anthony RowlandThe effects and extent of the harmful algal bloom became more obvious when it impacted Encounter Bay and the southern surf coast in March. Coinciding with dead fishes and invertebrates washing up, suspected toxins in the oceanic surf aerosol and foam caused respiratory issues, headaches, vision problems and other reactions in surfers, beach goers and coastal residents in the area.

Those temporary symptoms experienced by people on the surf coast match those in other countries where Karenia blooms have hit surf beach areas. Karenia toxins present in ocean aerosols and foam cause irritation and other effects if inhaled or ingested. Discoloured sea foam in the water or on the beach during a bloom period is a visible indication. During the main human impact period in March and April, the EPA in SA advised people to avoid the coastal area where symptoms were being experienced.

the toll on marine life

This HAB is impacting species in South Australia at all trophic levels - from shells to seals, and from sea worms to great whites. There are hundreds of species washing up, but many other affected marine taxa that are not, and are yet to be detected in subtidal surveys. There is evidence of mortality in both inshore and offshore species.

Long-lived fish like iconic harlequinfish were among the many species reported to be affected by the bloom. Image: Caroline HornMaori octopus have been among the many cephalod species to suffer . Image: Caroline HornUnprecedented Elasmobranch Losses

The impacts of the Karenia HAB on South Australian marine life are unprecedented and widespread. Thousands of benthic sharks and rays have washed up dead or dying, many showing signs of internal haemorrhage (characteristic of Karenia impact). On one Kangaroo island beach alone, 100 sharks and rays were observed in a single day.

One of many—Port Jackson Sharks have been found washed ashore during the bloom event. Image: Lochie CameronSome of the most commonly recorded species washing up around the central SA coast include fiddler rays, Port Jackson sharks, shovelnose rays, cobbler wobbegongs and large smooth rays, amongst others. Pelagic sharks are also dying from the physiological effects of the bloom cells – white sharks, bronze whalers, gummy, whiskery, and other species. Dead sharks are continuing to wash up in various parts of SA over autumn 2025, from the lower south-east of SA through to the gulfs.

Too Slow to Flee: Habitat-Linked Mortalities

Seadragon at Stokes Bay, Kangaroo Island. Image: RAD K.I.Fishes of many species have been dying, especially those that live on reefs, in seagrass beds, on the sea floor or in the benthic sediments. That is expected because these species are strongly habitat-associated, and many are slow-moving and cannot swim away during the life and death cycle of the bloom cells. Some of the most commonly observed mortalities over autumn have included cowfishes, leatherjackets, boarfish, weed whiting, scalyfin and rock cod.

Legislatively protected leafy and weedy seadragons are also dying from the Karenia HAB, and populations in the upper south-east / Encounter bay islands, Kangaroo Island and southern Yorke Peninsula have likely been impacted for years to come. The multiple seadragon deaths have occurred before the spring and summer egg-carrying periods. Many breeding age adult seadragons have died, and will not contribute to creating the next generation of this iconic species.

Invertebrate Die-Offs and Habitat Decay

Many invertebrate groups have also been affected, including mass death of Goolwa cockles, and washups in bloom-affected areas of octopus and cuttlefish, sea cucumbers, crabs, sea snails and many other species. Karenia microalgae also cause the death of attached filter-feeding species such as sponges and ascidians, and divers have observed decay and death of the colourful sessile invertebrate cover in at least one popular dive location. Impacts on seagrass and canopy seaweeds have not yet been determined in South Australia, but significant declines in kelp cover were observed in one part of Japan, after a 2-month long bloom of a less common Karenia species.

Anthony Rowland with a dead cuttlefish retrieved from the surf at Victor Harbor. Image: Caroline Horn)What’s Fueling the Bloom?

Harmful algal blooms (HABs), including toxic dinoflagellates such as species in genus Karenia, have increased around the world in recent decades. Globally, Karenia blooms are triggered by numerous oceanographic conditions, but some consistent precursors in other countries include higher than average sea temperatures (e.g. 2.5 – 3 degrees higher in SA waters in autumn 2025), higher than average air temperatures (up to 10 degrees higher than long term average in SA, in autumn 2025), consistent periods of low winds and calm seas to promote bloom growth during the heat wave conditions, and a nutrient source to feed the microalgae.

Sea Surface Temperature Anomalies (6 day average) on 12th of March 2025. Data and imagery sourced from the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS), accessed via OceanCurrent.Two of several major nutrient sources have been potentially implicated but not proven as partly driving the initial late summer / early autumn bloom in SA. The hypothesised sources include the annual ocean upwelling of nutrient-rich deeper waters (particularly strong in the summer of 2025); and the nutrients emptied into the upper south-east / Goolwa area in January 2023, following a major Murray River flood.

Regardless of initial nutrient source, the bloom has expanded into other SA waters that also remain unseasonably warm, and new blooms can utilise other nutrient sources in those areas. Whilst temperature anomalies and nutrients are often main drivers, there is also research evidence overseas showing that increase acidity (dissolved CO2) promotes the growth and possibly increases the toxicity of Karenia blooms. Thus, increased ocean acidity over time could favour the growth of these HABs.

The Science of Toxicity: How Karenia Kills

Globally, there is increasing research evidence showing how Karenia dinoflagellates of several species cause widespread death of marine life, in many ways. This includes harmful effects of the bloom cell concentrations in the seawater; the reactions of marine species to the whole cells when they enter the gills or other parts of the body; disruption of oxygen pathways; the physiological impacts that can occur - such as damage of gills and other tissues, and immune reaction to the presence of the cells and their toxins; internal cell damage in the body (including haemorrhaging from red blood cell rupture), and, over the longer term, bioaccumulation up the food chain from concentrations of Karenia toxins in organs.

Blue Crab with egg mass and Scolecenchelys worm eel. Images: Lochie CameraonThere is also research from the US showing that over time, the toxins from Karenia in bloom-impacted locations can be stored in marine sediments.

Unseen from Shore

Largely unseen is the damage to benthic cover, such as habitat-forming hard bottom / shell species; other attached fauna such as sponges; heavier reef species that do not often wash up, and habitat-forming marine plants. An exception is the important imagery and information about the effects of the Karenia HAB observed by recreational divers in early April, who witnessed and documented devastating scenes at a favourite jetty dive site.

Dead volute snail and garfish captured underwater at Edithburgh, Yorke Peninsula, SA by Paul Macdonaldhow you can help

We encourage anyone who finds dead marine life either on the beach, or in the water to take photos and upload to the citizen science portal iNaturalist. The photos will be imported into the 2025 SA Marine Mortality Events project database, and used in ongoing research and public information. This project , started by Ozfish SA’s Brad Martin and co-managed by Brad and Janine Baker, is a major part of the ongoing community effort to document the bloom impacts. There are now almost 200 contributors around South Australia, plus iNaturalist-based projects in some regional areas too, such as Kangaroo Island

We can all help - beachcombers, fishers, divers, snorkellers, surfers, rock poolers and anyone else on the coast or in the water in bloom-affected area. As well as photos, estimating the number of each species is also very helpful for those who have time to document (e.g. ‘4 dead octopus seen during a dive’; ‘3 dead fiddler rays seen in the shallows’; ‘300 cuttlebones counted over 100m stretch of beach’). That information can be added in the Description box during the iNaturalist photo uploads.

All citizen science contributions are helpful in understanding the scale and impacts of this unprecedented event. It is important that there is a secure, long-term, publicly accessible repository of evidence over space, time and by species group.

after the bloom: tracking change

Over the longer term, the Reef Life Survey (RLS) program will be an important tool for understanding the subtidal impacts on species and habitats in bloom-affected areas. RLS transect data have been taken over years, in previously unaffected locations, so comparisons of before and after data will be important in understanding the HAB-mediated damage, and the ecological impacts that will result over time. Underwater drones / ROV and Go-Pro footage will also be helpful, and those who have access to these tools are encouraged to record when safe to do so, and keep the footage until an agency can receive and extract the important visual information.

Many breeding age adult seadragons have died, and will not contribute to creating the next generation of this iconic species. Image: Anthony Rowland.See It. Record It. Share It.

The wash-ups that are being recorded in iNaturalist are one of several main ways in which citizen scientists can help. Other ways include timely reporting to PIRSA and NPW of new observations, especially in areas where impacts were not previously recorded. It is recommended that people ring National Parks and Wildlife if they find dead seals, dolphins, penguins, or sea birds, so that carcasses can be collected for pathology and toxicology.

The large number of fishes, benthic sharks and rays and marine invertebrates washing up in multiple locations across SA reduces the opportunity for PIRSA Fish Watch officers to collect all potentially relevant examples, but it is important to ring Fish Watch if large aggregations of dead marine species are observed, or if mortalities are noticed in previously unrecorded areas. Also, pelagic sharks such as white, bronze whaler, gummy sharks, whiskery sharks and others are being collected for necropsy.

The remains of an Angel Shark by Lochie Cameron and juvenile common thresher shark that washed ashore between Moana and Seaford by Charlie HuveneersAny washups of pelagic sharks should be reported as soon as possible, as should any odd behaviour, such as oceanic sharks showing signs of distress in very shallow waters. If the carcass is very fresh, there is a better chance of specialists determining exactly how the shark died.

We Are the Record Keepers

‘All eyes on the beach and in the water count’. All of us have an opportunity to ensure that the deaths of our beloved Great Southern Reef species do not go unrecorded, nor the damage to marine habitats and ecosystems across SA. The impacts of this extensive, harmful algal bloom are testament to long-term, increasingly evident climate-mediated change in southern Australian waters.

The same mass deaths of marine life from Karenia and other blooms have occurred in other countries in recent years, and are continuing. Decades ago, an increase in harmful oceanic algal blooms was predicted, driven by climate-change conditions. We are now living in that time.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Janine Baker is a marine ecologist and educator with 35 years of experience in South Australian marine research. She is an expert in species identification and biodiversity of the Great Southern Reef, contributing significantly to marine conservation efforts. Janine coordinates long-term citizen science initiatives, including the Dragon Search South Australia project and the Marine Hitchhikers projects, that engage divers, snorkellers, beachcombers and others in documenting marine life. Janine’s work bridges scientific research, marine education and community involvement, aiming to protect and understand the rich marine ecosystems of southern Australia.

Understandably, many are feeling overwhelmed and asking: what can we do? Below are some meaningful ways to respond and take action:

1. Those on the front line: Log sightings on iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/.../sa-marine-mortality... Every entry helps scientists understand what's happening and respond to change in real time.

2. Add your voice to our formal submission. We’re collecting statements from community members, coastal residents and any concerned Australians to present directly to South Australian and federal decision makers. https://form.jotform.com/251377469607064

3. Join the ‘Science of the algal bloom’ Webinar on the 28th of May hosted by the Port Environment Centre.

4. Advocate for Climate Action. Both divers and non-divers, sign the Divers for Climate National Statement at diversforclimate.com/imadiverforclimate that calls on leaders to step up with stronger climate action for our oceans.

5. Stay informed and Educate Others. Follow updates from trusted sources, and remember that collective action is powerful.

you may also like: