giant australian cuttlefish

The Spencer Gulf’s Annual Cuttlefish Aggregation

Giant Australian Cuttlefish are the largest cuttlefish species in the world.

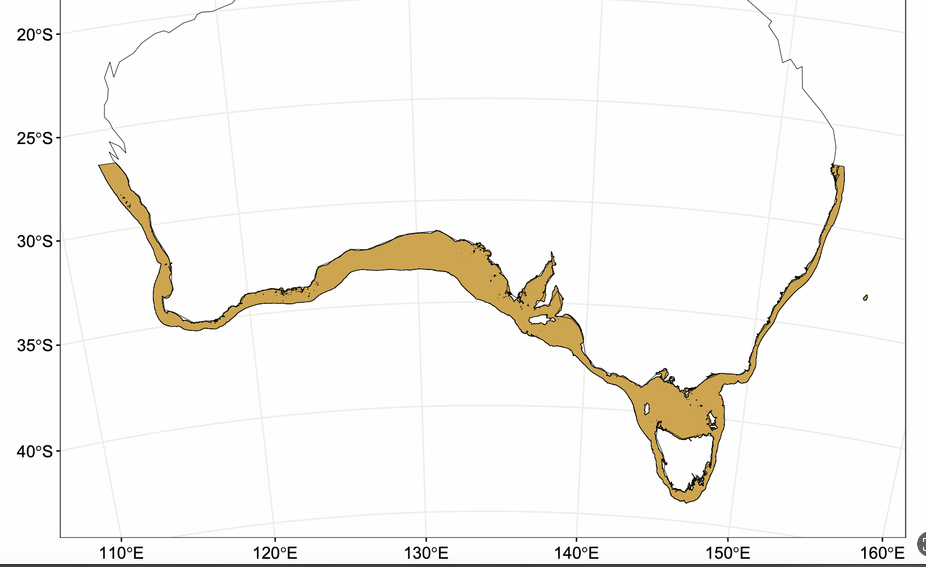

Although they can be found all along the Great Southern Reef, there is a distinct population that gather in large numbers each winter along 8km in South Australia’s Northern Spencer Gulf.

This section of rocky reef provides an important breeding ground for the Giant Australian Cuttlefish (Sepia apama), and it is within and underneath these rocks where the cuttlefish lay their eggs.

The basics

Making a move

Males compete for access to females, rather than defending egg-laying sites. Large males that successfully pair with a female often guard her closely, using vivid colour changes and dynamic displays to ward off rivals. Smaller, unpaired males spend much of their time roaming the reef in search of solitary females—or attempting to sneak mating opportunities with those already paired.

Fussy cuddlers

Mating involves a head-to-head embrace, during which the male transfers sperm packets to the female while jetting water toward her mouth area. Afterward, males may guard the female to prevent rival matings and may even flush out competing sperm to increase their own chances of fertilisation.

Females don’t lay eggs immediately and often mate with multiple males before beginning to deposit eggs under rocks or in crevices. They move between sites, laying 5–39 eggs per day. The developing eggs, fertilised by different males, hatch after 3–5 months—typically between mid-September and early November.

Strength vs. stealth

Smaller male cuttlefish use a range of clever strategies to access mates. These include open stealth—approaching a guarded female while the dominant male is distracted; hidden stealth—seeking females beneath rocks and reef cover; and female mimicry—disguising themselves as females to avoid detection or aggression from larger males.

Annual Aggregation Timeline

-

Early Arrivals

As water temperatures begin to cool, the first cuttlefish start to arrive in the rocky reef areas near Point Lowly and Whyalla. These early individuals scout the best breeding spots beneath the rocks. -

Mass Aggregation

Tens of thousands of Giant Australian Cuttlefish gather along an 8 km stretch of reef. This is the peak of the breeding season, where males compete for mates using colour-changing displays, camouflage, and mimicry. -

Life Begins Beneath the Rocks

Females carefully deposit clusters of eggs in sheltered crevices and under rock ledges. Each egg is attached individually and camouflaged to blend with its surroundings, protecting it from predators. -

Departure and Decline

As spawning concludes, the adult cuttlefish begin to die off—a natural end to their short life cycle. The reef becomes quieter, though eggs remain hidden and developing. -

New Generation Emerges

Hatchlings begin to emerge from the eggs, starting life independently in the shallow waters of the Spencer Gulf. They will grow and disperse, feeding and maturing over the next year. -

Return to Spawn

After about 12–18 months, the surviving juveniles return as adults to the very same reef to spawn—completing one of nature’s most remarkable annual migrations.

tracking trends

Each year, scientists from SARDI Aquatic Sciences survey the Giant Australian Cuttlefish population at Point Lowly. Divers swim 50-metre transects, counting all cuttlefish within one metre on either side to estimate population density. In peak season, several hundred cuttlefish can be recorded in a single transect.

Boom and Bust

In the late 1990s, the Giant Australian Cuttlefish population was estimated at around 180,000 and appeared stable. By 2013, numbers had plummeted to just 13,000—a decline of over 90%.

The sharp drop sparked concern and speculation. Possible causes like pollution, disease, aquaculture, and fishing were investigated, but scientists struggled to identify a clear link to the decline, given the area's multiple uses and pressures.

precautionary principle

While studies show no definitive link that fishing pressure caused the cuttlefish population to decline, it was more of a precautionary approach to implement protective bans on fishing in the breeding areas.

From 1998 onwards, the sanctuary zone within the aggregation site has been in place. In March 2013 following record low levels of cuttlefish, the entire northern Spencer Gulf (the line between Wallaroo and Arno Bay) was closed to the taking of the species.

the temperature theory

What studies did find was that the cuttlefish embryos develop at a rate that is parallel to the temperature at which they hatch. Researchers found that during years when the populations increased, the embryos hatched into warmer temperatures. In warmer conditions the growth of the juvenile cuttlefish speeds up and they may become less vulnerable to predation. During years when populations were suppressed, they developed through cooler temperatures, therefore, their growth was slower and perhaps they were more vulnerable to predation.

rockstars of the sea

Cephalopod populations are known to show considerable fluctuations in abundance, with variations including 10-20 year cycles. When analyzing impact, it is important to recognise their short life span (12-24 months) and the single spawning life history of the giant Australian cuttlefish. Any species with this reproduction strategy is particularly vulnerable since there is no ‘storage effect’ within the population. As a ‘live fast die young’ species, this means they can be highly responsive to environmental stress, causing them to boom and bust dramatically.

rapid recovery

After a fast comeback in recent years, the aggregation continues to thrive. In 2020, the management removed the temporary ban of fishing cuttlefish from the entire northern Spencer Gulf, and will continue to monitor the aggregation closely.

The local town of Whyalla has really embraced this annual event – after all it is the only place in the world you are able to see tens of thousands of cuttlefish aggregate in such a small area. While this year only South Australians had the luxury of being able to dive with these magnificent animals, we all hope that this is something that will continue to be a huge drawcard for local and international tourists visiting the Great Southern Reef for years to come.

May 2021 update

In the lead up to the 2021 season, in addition to the permanent cephalopod closure in False Bay, from 14 May to 10 August 2021, a temporary cephalopod fishing closure is in place in an adjacent area.

The temporary closure area includes all waters bound by a line commencing from the Point Lowly Lighthouse and following the eastern boundary of the existing closure area to 100 metres offshore from the high water mark and then following the coastline to a point 100 metres south of the boat ramp breakwater near Port Lowly.

Highest Level of Protection

In May 2023, the State Government has made a ban on cuttlefish fishing in the Upper Spencer Gulf permanent to protect this one-of-a-kind breeding event. Fishers must not target or take any cuttlefish species in the waters north of a line from Northern Spencer Gulf north of the line between Arno Bay and Wallaroo.

This is a much needed win to ensure the highest level of protection for this world-class spectacle. The ban was removed in 2020 by the previous state government but was re-instated temporarily in 2022.

national heritage protection

To highlight the National significance of this site, the Cuttlefish Coast Sanctuary Zone was given National Heritage status in May 2023. This status will provide further protection of this spectacular breeding event as well as support further research into the species.

For the classroom:

access the giant australian cuttlefish lesson

Watch: Kids see giant cuttlefish mating. This is how they react

you may also like: