emma church

Decoding Ocean Stewardship for the Great Southern Reef

Research Fellow Emma Church is driving an innovative approach to understanding ocean stewardship within the Great Southern Reef Research Partnership. With a background in environmental social science and a lifelong passion for the ocean, Emma is working to bridge the gap between science and public action, finding new ways to engage and motivate people to protect one of Australia’s most biodiverse and underappreciated marine ecosystems.

Emma’s work combines behavioural science, social engagement, and ecological insight to explore what drives conservation actions and how to inspire meaningful change. Read on to discover how Emma is redefining stewardship for the Great Southern Reef.

from coral to kelp

Emma grew up surrounded by the ocean, through family trips to the Great Barrier Reef, where she spent countless hours snorkelling alongside sharks and tropical marine life. But today, her fascination has shifted to cooler waters, where she works on the socio-ecology of Australia’s Great Southern Reef.

Since moving to Tasmania, Emma has embraced freediving, immersing herself in the vibrant and unique temperate waters of the GSR. “The kelp and all the creatures, the colours—it’s just amazing,” she says.

understanding what motivates stewardship

Emma has always been fascinated by human behaviour—what we do, why we do it, and, importantly, what influences our choices when it comes to the environment. Her masters research gave her the tools to examine these influences closely, from individual habits to societal norms, and revealed how mindful, intentional actions could support pro-environmental behaviour. Throughout her PhD she continued to explore what drives people to engage in pro-environmental behaviours and how social capital can influence these actions.

After finishing her PhD, Emma’s transition into the GSRRP was a natural progression. “It was a perfect fit,” she reflects, describing how her background in human behaviour aligned with the GSRRP’s mission to protect the reef through social science, communication, and ecological research. As a key member of the socio-ecology team, she collaborates with an expert advisory panel, including Prof Gretta Pecl, Prof Natalie Stoeckl, Dr Angela Dean, and Dr Emily Ogier, to apply insights from behavioural science to marine conservation.

Together, they’re working to address one of the GSR’s most pressing questions: How can people be inspired to take stewardship of Australia’s temperate waters—an environment that is remote, often unseen, and increasingly vulnerable to the pressures of climate change and human activity.

Addressing Key Conservation Questions

Emma’s research centres on understanding who is most likely to embrace stewardship and how to encourage more people to participate in protecting the Great Southern Reef. She’s looking at individual actions as well as considering how organisations and policymakers can be engaged. “We’re focused on finding out what practical actions people can take and how to connect with those most eager to do them,” she explains.

Collaborating with Dr Melissa Hatty and Dr Mark Boulet from BehaviourWorks Australia, Emma and her team are honing in on specific pressures affecting the GSR and looking at what drives certain behaviours within different groups. “It’s about identifying the problems and understanding the behaviours that impact the reef, ranking them, and seeing where we can make the biggest difference,” she notes. Her work is about finding targeted ways to help people, organisations, and policymakers see their unique roles in supporting the GSR.

Establishing Key Threats and Baseline Surveys

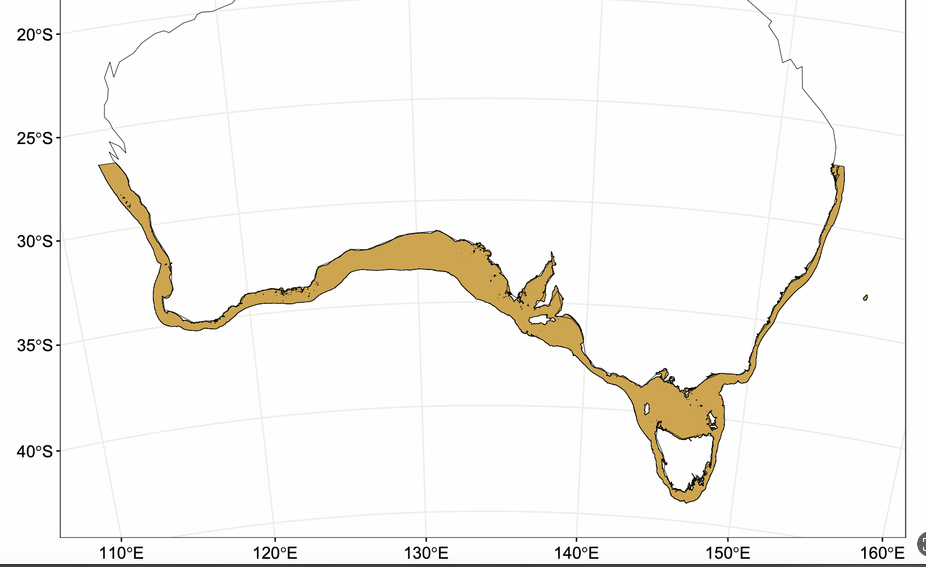

Emma and her team have already made significant traction identifying and ranking the GSR’s key threats, drawing on the State of the Environment report, other research tools and advice from the Great Southern Reef Research Partnership. Climate change and fishing related pressures emerged as significant issues, and this preliminary work has allowed them to narrow their focus. “The Great Southern Reef is a big, complex area,” she explains. “There are so many pressures, so narrowing it down is essential for developing meaningful interventions.”

Next on Emma’s agenda is sending out a baseline survey that will capture the views of people who live along Australia's south coast, including their interactions with and knowledge of the GSR. This survey is a critical step in her research, she says, as it will allow her team to understand how people value the reef, the ways they already interact with it, and any conservation behaviours they’re already practising.

“We’re looking at a broad range of questions—what people know, what they care about, and what they’re doing. This will be the basis for everything else,” Emma shares. The survey will help her identify key audiences and develop tailored messaging to engage each group effectively.

Developing Behavioural Interventions

One of Emma’s goals is to design behavioural interventions tailored to specific audiences, with the dual aim of reducing damaging behaviours and promoting conservation actions. One way of doing this is to focus on message framing, using different approaches to see what resonates most with people.

For instance, she might frame a message around the “wonder and the problem” of the GSR, presenting stunning imagery of the reef’s biodiversity alongside information on threats it faces. Another framing could include a clear action step, such as supporting sustainable fishing practices.

Emma points to the example of encouraging urchin consumption as a way to control overpopulation. “If admired chefs start promoting urchin dishes, it could create a ‘halo effect’ that makes this behaviour desirable,” she says, underscoring how social influence and carefully chosen messages can make a conservation action both appealing and impactful.

The Role of Imagery, Film, and Social Media

Emma sees imagery, film, and social media as essential tools for engaging people with the GSR, especially given its remoteness and the unfamiliarity many feel toward temperate marine environments. “Imagery and film have this powerful ability to transport people,” she explains, emphasising that visuals can bring the reef’s beauty, diversity, and challenges into the everyday lives of people who might never visit it. Social media, in particular, allows her to amplify these visuals and create a digital community united around a shared responsibility to protect the reef.

Emma draws on the concept of “social norms”—the unspoken rules about what behaviours are seen as acceptable or ideal—to craft messages that resonate. “People look to others, especially admired figures, to understand what’s acceptable or expected,” she says, describing how influential figures can model pro-conservation actions. For example, showcasing chefs, divers, or conservation advocates actively engaged in reef-friendly behaviours can inspire audiences to mirror these actions, creating a ripple effect of positive change.

However, Emma is mindful of how visuals are paired with messages to avoid contradictory signals. One example, she has observed, is a ‘cute’ photo of someone petting a dolphin paired with a message urging people not to feed or touch wild dolphins. “Mixed messages like these can cancel each other out,” she explains, as the imagery unintentionally reinforces the very behaviour the message is trying to discourage. Instead, Emma aligns each visual with a consistent, clear message to ensure conservation norms are strengthened, not undercut. This careful framing is central to her work, ensuring that imagery and messaging work in harmony to foster respect, awareness, and action for the GSR.

Guiding Emotions into Action

Emma is also interested in the emotional drivers of stewardship and behavioural change, exploring how feelings like wonder, sadness, and hope can be harnessed to motivate action. “If people feel a strong emotion, they need a clear path forward,” she explains. Emma encourages the use of messaging strategies that combine imagery that evokes wonder and beauty, followed by information on the challenges and a call to action. “It’s about giving people something they can do with that feeling,” she adds. She believes that directing emotions into constructive actions—whether through personal habits or advocacy—can build a powerful base of support for the GSR.

At the same time, Emma encourages people to think about their “sphere of influence.” Stewardship can be part of daily life, from how we manage waste to how we vote. “There’s a systems-level influence we can all tap into,” she explains. Whether it’s choosing sustainable seafood, advocating for climate policies, participating in citizen science or simply normalising talking about climate change, every action contributes to a culture of stewardship. By taking small, intentional steps within our personal lives and communities, Emma believes we can create a collective impact that drives meaningful change, protecting the Great Southern Reef for generations to come.

This work is supported by funding from the Ian Potter Foundation and the Centre for Marine Socioecology. Additional support has been provided by the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) and the University of Tasmania (UTAS)Meet more gsr Scientists

you may also like: