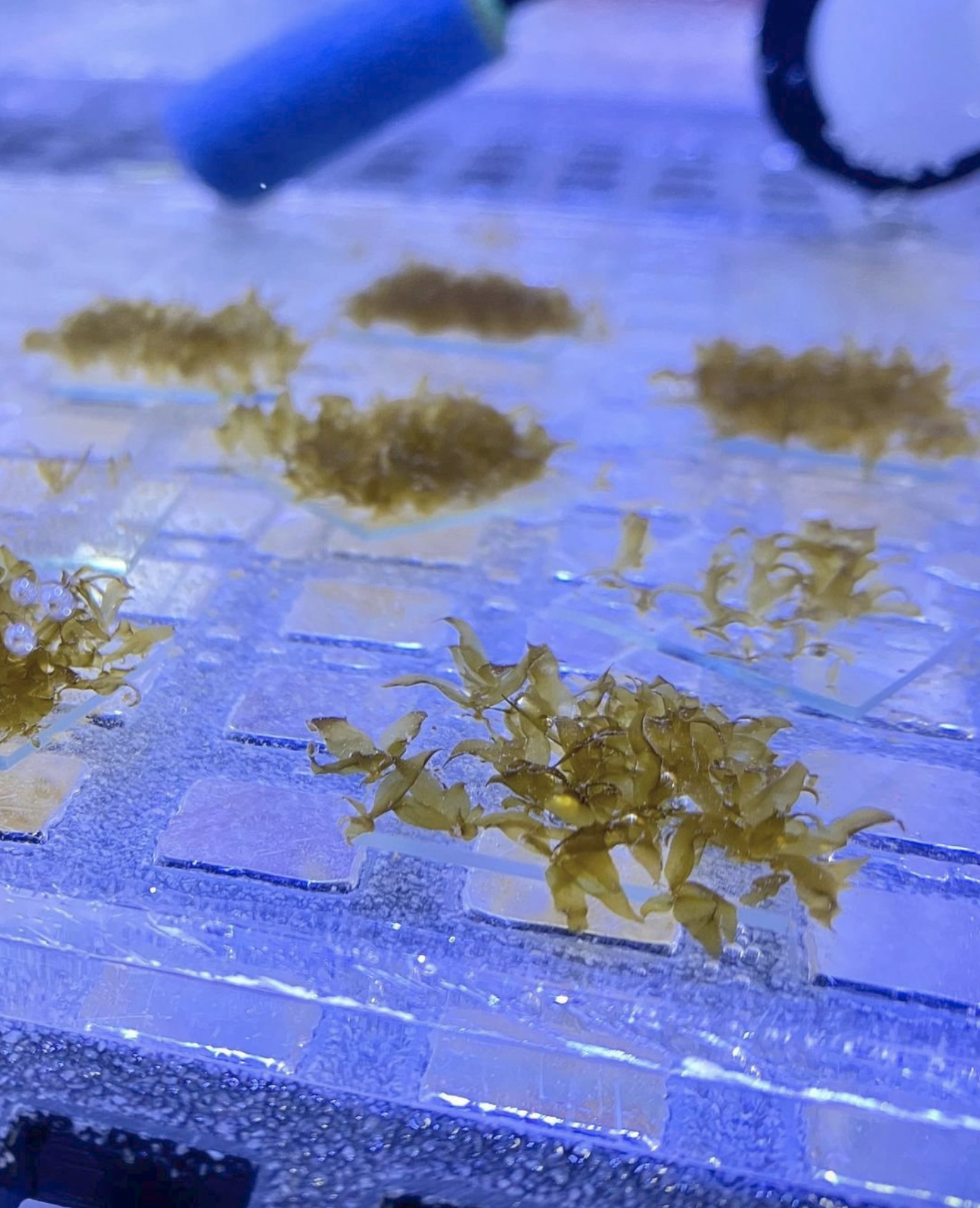

golden kelp

What makes a reef?

Just like the Great Barrier Reef, the Great Southern Reef is a long network of hundreds of individual reefs. The reefs, which make up the Great Southern Reef, are known as temperate rocky reefs.

Golden kelp (ecklonia radiata) forms the backbone of the Great Southern Reef.

Kelp and other seaweeds are primary producers.

They form the basis of the food chain by capturing the suns energy and creating food through photosynthesis.

Seaweed is the common name for marine algae, sometimes called macro algae. Even though they may look like underwater plants, seaweeds are not plants at all.

Like plants though, kelp forests also harness the power of the sun to grow, produce oxygen, and capture carbon dioxide (CO2).

Scientists refer to kelps as foundation species.

This is because they create habitats that benefit other organisms. Kelp forests are made of brown seaweed (including species like golden kelp, giant kelp and bull kelp) which produce thriving underwater cities filled with animals from the smallest snail to the largest whale.

Photo: Gergo Rugli

These seaweed covered reefs form a home to a huge range of critters… fish, crustaceans, shellfish and other seaweed species. Many of these species we harvest either recreationally or commercially and are of huge economic value to Australia. For example, the Rock Lobster and Abalone which are both highly dependent on kelp forests.

So what is kelp?

Not just your average seaweed

Kelps are much larger and more structurally complex than most other seaweeds. They belong to the order Laminariales and can grow very large, canopy forming, dense underwater forests. Kelps are known for their rapid growth rates, which can be much faster than those of most other seaweeds. This rapid growth is facilitated by their ability to absorb nutrients efficiently in cold, nutrient-rich waters.

Kelp holds on

Besides living underwater, kelp forests have many differences to land plants. They have no roots and instead capture vital nutrients from the water via any part of their tissue. What look like roots are actually "holdfasts" - structures that help stop the kelp from washing away.

It is a carbon sink

A carbon sink is a natural system that sucks up and stores carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Fast-growing oceanic jungles of kelp and other seaweeds are highly efficient at storing carbon.

A recent study found that raising seaweed in just 0.001 percent of seaweed-growing waters worldwide and then burying it at sea could offset the entire carbon emissions of the rapidly growing global aquaculture industry, which supplies half of the world’s seafood.

A worldwide ecosystem

Kelp forests cover over 1/3 of our world's coastlines and cover more area than coral reefs, seagrasses, or mangroves.

It is closer than you think

Over 750 million people live within 50 km of a kelp forest. If you are from London, LA, Sydney, Tokyo, NYC, Cape Town, Seoul, or Santiago, you even have a kelp forest in your blue backyard.

Kelp requires balance

We must always make sure that we leave enough top predators in a kelp forest. Otherwise, there are no organisms left to eat the things that eat kelp. The results are devastating as a bountiful kelp forest can be transformed to an underwater desert.

The Kelpers

Australian researchers are working at the global forefront of marine habitat restoration, with projects underway in every state along the Great Southern Reef.

An expensive endevour

Habitat restoration is a resource intensive exercise used as a last resort for areas where vital habitats have been lost or are in decline and natural recovery is not occurring. Currently there are active restoration projects on the GSR working to restore seaweeds, seagrasses, and oyster reefs.

Green Gravel

Green Gravel, a concept that integrates restoration ecology with the natural process of seaweed reproduction, offers an impressive potential for the restoration of kelp forests on a large scale. The method is simple yet ingenious: marine substrates or 'gravel' are seeded with juvenile seaweeds, which are then scattered across degraded marine habitats.

Collaborative cultivation

Phd and senior lecturer at Deain University, Prue Francis, spearheads the active cultivation and restoration of golden kelp within Port Phillip Bay, focusing on nurturing its early life stages through innovative techniques at the Deakin facility in Queenscliff. Referred to fondly as growing "kelplings," this process involves experimenting with substrates like gravel and twine and typically takes around eight weeks before the kelp is transferred to The Nature Conservancy for underwater planting. Collaborating with key partners including Deakin University, Parks Victoria, and the University of Melbourne, this multifaceted initiative extends beyond cultivation and planting to encompass monitoring progress and planning for future deployments, emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach.

Funded generously by the Victorian Government's Department of Energy, Environment, and Climate Action, the project has garnered significant interest from local organizations and citizen scientists eager to contribute. Francis underscores the necessity of addressing broader challenges such as ocean warming and water quality alongside active restoration efforts. To complement these endeavors, a separate initiative funded by the Port Phillip Bay Fund focuses on biobanking, preserving biomaterial from declining kelp populations for future use, thereby ensuring a more sustainable and resilient restoration strategy.