Harmful Algal Bloom in South Australia

SPRING SITUATION

By Janine Baker

Marine Ecologist & Educator, for Great Southern Reef Foundation

The extensive harmful algal bloom (HAB) that wreaked havoc over thousands of kilometres of South Australia’s marine environment, has continued into mid-spring in some parts of the State. Great Southern Reef Foundation provided detailed reports on this unprecedented algal bloom in April and July.

Since that time, metropolitan Gulf St Vincent and parts of Yorke Peninsula and western Spencer Gulf continue to be affected. Some part of southern Yorke Peninusla, Kangaroo Island and the Encounter surf coast that were severely impacted in autumn, are now heading towards the long, uncertain and largely undocumented process of recovery.

Chlorophyll concentration map from CopernicusEU Sentinel-3 on 13 August 2025 many Genera Detected

Within the metro Adelaide coastal waters, data from phytoplankton specialists have shown ‘pulses’ of harmful Karenia dinoflagellates blooming and dying over the weeks and months. Whilst the location and relative density of phytoplankton can be tracked by satellites and confirmed by water samples, the exact agents and the mechanism of their harmful actions are still being investigated.

Across the central South Australian coast, the bloom remains dominated by a mix of Karenia species – some confirmed early and others identified more recently, and these have been blooming at hundreds of thousands to millions of cells per litre in some locations.

Karenia mikimotoi was identified early in the 2025 bloom cycle, and now in spring the little-known South African species Karenia cristata has also been isolated, thanks to ongoing culturing and molecular genetic work by a team of researchers led by Professor Shauna Murray at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS). The UTS lab collaborated with scientists from IMAS (University of Tasmania), Microalgal Services, the University of Queensland, SARDI, the Cawthron Institute, NSW DPIRD, and others. Karenia cristata has been confirmed as a primary producer of brevetoxins in the 2025 South Australian algal bloom. It appears to have been one of the dominant species throughout much of the event, previously reported only as Karenia sp, along with K. mikimotoi and other dinoflagellates in the publicly-available counts data.

Other harmful Karenia in the South Australian HAB include K. longicanalis, K. papillionacea, and K. brevisulcata. The bloom mix comprises lesser quantities of other harmful dinoflagellate species, in the genera Karlodinium, Katodinium, Gymnodinium and related groups. This important research on 5 harmful Karenia species and other relatives in the SA bloom was undertaken in record time by UTS and colleagues.

Each of these dinoflagellates contain specific toxins, but their combined actions when they co-occur in the same marine waters, are not known. Some of these algal species can harm at low densities, and the unpredictability and severity of this multi-species bloom has become frighteningly clear over the months. In some ways, the bloom is “self-perpetuating” - many of the species can both produce their own food from sunlight but also concentrate and fix carbon from the water, for growth and toxin production.

WHAT’S STILL LIVING IN GULF ST. VINCENT?

Port Jackson Sharks, which often begin aggregating for mating in Gulf St Vincent in Spring, by Stefan AndrewsAs the HAB raged on into winter, close to 90% of the 11,800 community records during July came from metropolitan beaches, where more than 500 people photographed the early winter mortalities. Fiddler rays, Port Jackson sharks, shovelnose rays; a multitude of fishes from reefs, seagrass beds and sand habitats; razorfish, abalone, trough shells all died and washed up, and the long list goes on.

In metro waters of eastern Gulf St Vincent, some species were recorded early in the bloom cycle, such benthic sharks and rays, sand-dwellers such as worm eel fishes, peanut worms, and burrowing sea cucumbers and bivalve molluscs that support seaweeds. Some species have continued to wash up in Adelaide waters for months, such as the leatherjackets, weed whiting and flatheads. For others, where was a delay in observed mortalities, likely from populations suffering sub-lethal impacts in the early stages of the bloom, but eventually succumbing.

The onslaught continued over August and September, and questions that would have seemed absurd pre-bloom, now warrant closer investigation:

Do sharks and rays still live in Gulf St Vincent?

Will the razorfish beds ever recover?

Are there any live seadragons left?

Where have all the calamari gone?

latest impacts

Throughout September, leatherjackets continued to wash up in the thousands, particularly schooling, scavenging species such as juvenile bluefin and rough leatherjackets, fishes that are part of “nature’s clean-up crew”. Sadly, all life stages are being observed dead on beaches, from young-of-the-year through to large adults of both sexes. Larger reef leatherjackets such as spinytail and six-spine have also washed up in abundance.

A common sight across Gulf St. Vincent beaches in recent months: high densities of small leatherjacket fish. Seagrass-dwelling fishes such as blue weed whiting in Gulf st Vincent continued to be killed by the bloom over spring. Some of the common, shallow water reef fish species in Gulf St Vincent have also been affected. Examples include long-snout boarfsh, talma, scalyfin and old wife.

Blue Weed Whiting at Tennyson Beach by Andy Burnell Crab.e.camSlow-swimming, site-associated fishes such as cowfishes and pufferfishes continued to wash up in abundance. These fishes have small gill slits that would easily be clogged by the dinoflagellate cells. No studies have been undertaken to determine the impact of whole Karenia cells when in direct contact with these scale-less fishes. The cowfishes can secrete their own lethal toxins through the skin when under stress.

Abalone wash-ups at Glenelg by Johanna WilliamsMany kinds of crabs have washed up in waves of abundance over the months, with spring sightings dominated by rough rock crabs, large spider crabs, decorator crabs and sand crabs. Abalone continue to die around bloom-affected regions, with almost 850 observations uploaded to iNaturalist since spring began.

Those community-reported abalone observations collectively represent thousands of individuals, particularly blacklip, staircase and circular abalone. The metro Adelaide coast provides a snapshot of abalone impact. From Outer Harbour through to Sellicks Beach records, there is a distinct time line, with most dead abalone wash-ups occurring 2 – 3 months after the bloom hit metro waters. For example, only 27 metro abalone records were uploaded to iNaturalist in June (compared with 2,257 records for all of that month in metro waters, representing 10s of thousands of mortalities of other species). However, by August and September there were more than 600 public reports in each of those months, of metropolitan area abalone deaths, representing thousands of individuals. The wash-ups have continued into October.

Dead spindle shells by Johanna WilliamsThe mass death of the large predatory Spindle shell Propefusus australis provides more evidence of the severe impacts of the HAB on seagrass-dwelling species. Almost 200 observations – from single shells to small aggregations counted over sections of beach – collectively represent hundreds of dead spindle shells. Surprisingly, despite the broad geographical distribution of both observers and the HA, 90% of these records came from metro Adelaide waters between Outer Habour and Sellicks Beach. Of all spindle shell recorded mortalities in 2025, 60% washed up between early September and the time of writing, second week in October.

Some environments have suffered worse than others during spring. In West Lakes, the now well- known Karenia mikimotoi was first detected in June, but since that time, a suite of harmful species in Kareniaceae has not left the Barker Inlet - Port River - West Lakes system. “Karenia sp.” counts peaked in late winter and the first month of spring, to millions of cells per litre (more than 10 million per litre at some sites in the Port River), but started to reduce by October.

Between winter and spring, extensive losses of bivalve molluscs (many species, large and small), gastropods (sea snails), sea stars, fishes, soft-bodied invertebrates and other fauna have occurred in the estuary and its tributaries. After half a year of the HAB in that system, the impacts of high concentrations of mixed harmful dinoflagellates on seagrass health and cover are also becoming evident.

Image: Dead Oysters at Snowdens Beach by Janine BakerLoss of an Ecosystem Engineer

The widespread loss of long-lived, sporadically-recruiting, structurally-supportive shellfish species such as razorfish Pinna dolabrata is of great concern. Due to limited investment in reproduction over the 2-decade life span, Butler et al. (1993) reported that razorfish populations cannot survive high mortality events. Around 1,000 records of dead razorfish – ranging from single shells through to aggregations of hundreds - have been uploaded to iNaturalist, collectively comprising at least tens of thousands of razorfish.

Major mortality events have occurred on north-eastern Kangaroo Island and both sides of Gulf St Vincent. Almost half of these washed up later in the bloom cycle, in September. Razorfish have a major role as “ecosystem engineers”, providing a hard surface for other species to grow on, in soft sediment habitats and seagrass beds. Attached organisms such as barnacles, hydroids, sponges, sea squirts, small seaweeds and native oysters grow on the razorfish shells, and also provide feeding and living habitats for various mobile invertebrates and small fishes.

The 3D structure of the razorfish themselves also provide shelter and breeding opportunities for marine life. The ecological implications of “whole bed” loss of razorfish are still being determined, but this structurally significant species should be a strong candidate for habitat restoration efforts, well into the future. Smaller numbers of other structural species such as hammer oyster Malleus meridianus - especially in metro waters, native Ostrea angasi oysters and have also been recorded in the beach mortalities.

Dead and living razorfish by Stefan Andrewsloss of living habitats

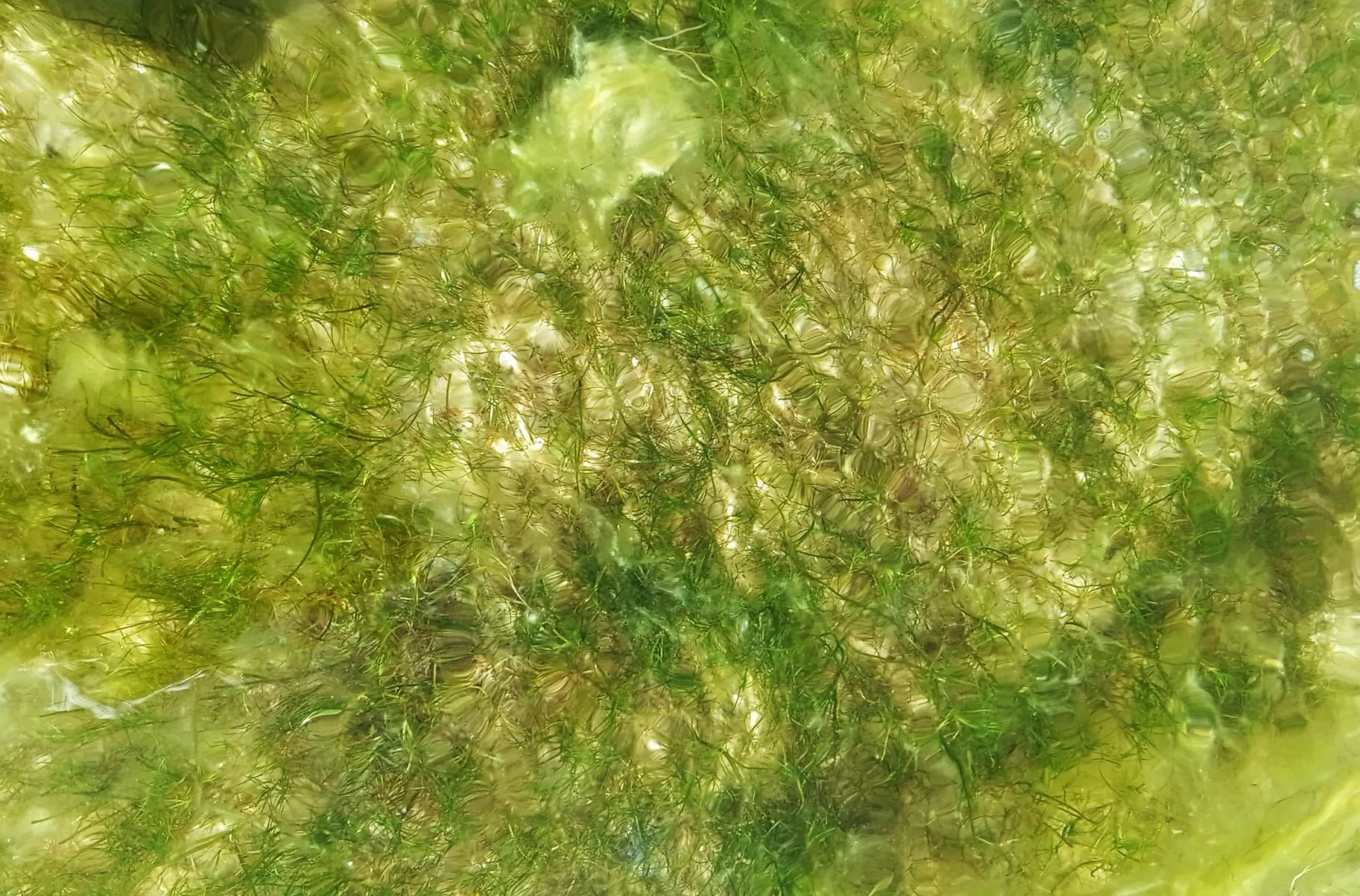

Equally concerning is the continued death and wash-up over spring of tonnes of seagrass - roots and all, brown canopy seaweeds and mixed red, green and brown seaweed understory in HAB-impacted areas. Living, structural habitat with many critically important ecological functions is being lost throughout 2025, in all seasons. That is still occurring at all scales: individual plants, populations, total biomass per area, and possibly also the future distribution and densities of many marine seaweeds. The June update provided more information about the ecosystem services of marine vegetation, and the impacts of harmful algal blooms on both seagrass and kelp.

That can include any or all of the following:

reduced potential for photosynthesis due to lower light penetration in areas where bloom cells have been concentrated in the water column since late summer;

related to the reduced photosynthetic potential - impacts on respiration and growth, from smothering of blades during dinoflagellate bloom death

bacterial and fungal build-up on blades of seagrass and branches of seaweeds;

cell and tissue death / necrosis from algal toxins;

degradation of supporting sheaths and root structures of seagrass, living in harmful bloom-contaminated sediments;

rain-down / sinking of mass quantities of dead Karenia cells and consequent increased bacterial loads in the sea floors. This contamination can change the sediment chemistry, reduce oxygen levels, potentially cause build-up of harmful gases, and result in ‘root rot’ and dislodgement of seagrasses.

Seagrass beds under stress in Upper Gulf St Vincent by Stefan Andrews and dead seagrass washups by Samantha Sea signs of resilience

In areas where the harmful bloom damaged habitats and biodiversity for months over autumn and winter, there are some signs of life - species that remained alive and have been photographed throughout winter and spring, and new recruits that are appearing at previously bloom-ravaged sites.

At Edithburgh and Wool Bay, divers participating in a multi-faceted community monitoring project have been recording the damage to (and loss of) attached biota on the jetty piles and sea floor, but also the indicators of resilience - species that survived months of Karenia-laden waters - and recovery. Even the appearance of a live stargazer - a large ambush predator that lives on the sea floor - is a heartening sign. These site-associated, long-lived fishes have been recorded dead in the hundreds in Gulf St Vincent over more than a half year of the HAB. Live adult cowfish, pufferfish and beaked salmon at Edithburgh also show that not all individuals of susceptible species succumbed.

The mollusc, crustacean and fish fauna in the Edithburgh area have been severely impacted since April. Six months on, spring photos of live sand crabs, blue crabs, gastropod shell eggs and young-of-the-year reef fishes such as brown-spotted wrasse, young talma, magpie perch and moonlighter offer some hope for future recovery of the reef fish fauna in that south-western side of Gulf St Vincent. Prior to the bloom, more than 115 bony fish species had been recorded by divers at Edithburgh.

Southern Cardinalfish (above) and Stargazer (below) at Edithburgh by Troy Johnson On the other side of the Gulf, Port Noarlunga Reef is a well- known, ecologically-valued marine sanctuary zone, frequently dived for decades. The HAB has taken a grim toll on both the reef and the nearby, species-rich Port Noarlunga jetty. In mid October, local diver Matt Tank reported wholesale loss of sponges, ascidians, anemones and sea stars; greatly reduced cover of kelp and other canopy brown seaweeds, and the usually abundant coralline algae missing from the understorey. Even the long, fern-like Caulerpa trifaria seaweed that showed signs of bloom-impact in August is now all gone.

But hope remains, with the sight of resilient fish such as silver drummer and zebrafish in small schools. The usual reef fishes and invertebrates at both Port Noarlunga Reef and jetty are few and far between, but sightings of brown-spotted wrasse, old wife, magpie perch, boarfish, gurnard perch and a red rock crab show that all residents have not been lost: whilst only singles were seen, others may be hiding in the low viz, green gloom.

Even the ubiquitous short-tailed Ceratosoma, SA divers’ favourite nudibranch, was gliding along over the grey sediment. Lean times ahead for these sponge-eating slugs, but they are survivors.

Gurnard Perch and Ceratosoma nudibranch spotted at Port Noarlunga by Matt TankThe bloom has impacted thousands of square kilometres of SA coastal waters, but some areas remain resilient. At the time of writing, the higher salinity waters of Northern Spencer Gulf remained free of the harmful algal bloom.

Early spring was a successful hatching time for the next generation of the iconic Giant Cuttlefish, and time will tell what fate awaits those recruits, as they travel south towards the Cowell - Wallaroo line, and north into Fitzgerald Bay.

Soon-to-hatch cuttlefish and hatched egg cases in October 2025. Images: Stefan Andrews - DEWRecently, divers have observed small numbers of leafy seadragons – singles or pairs at Fleurieu locations and up to 5 individuals per dive are being reported. During the current spring breeding season, it is hoped that the remaining individuals can find each other and help to create the next generation of this iconic species.

Seadragon spotted at Second Valley in September 2025 by Carl CharterThe Great Southern Reef December HAB update will showcase more of these signs of resilience, recovery and hope for the future.

A previous article in this algal bloom series discussed the South Australian citizen science community’s proactive, productive and extremely valuable responses to the HAB, right from the outset in early autumn.

Community members across bloom-affected regions have been involved with many projects over 2025, including some that have progressed and expanded over more than 6 months. Examples include:

Community Responses

Water sampling, training in sample analysis; HAB phytoplankton species identification using light microscopy (under tuition from expert plankton ecologists), and creation of a repository for community records. Phytoplankton identifications and counts from the community project are now also included in a combined source online dashboard, along with results from the SA government’s algal bloom water testing program

Finding, counting and photographing marine mortalities, and uploading to the community-based South Australian Marine Mortality Events 2025 project database on iNaturalist.

The ~ 70,000 records represent hundreds of thousands of individual deaths, out of the millions of visible marine species that have died in the bloom. Mass mortality numbers of small sand-dwelling shells and worms are not included in those figures, but examples are provided in the iNaturalist project.

These records, collected by at least 1,100 observers, are currently being prepared for analysis, and the creation of several public citizen science data analysis reports over the coming months. The first report will discuss the reported mortalities of sharks, rays and bony fishes over bloom-impacted geographical regions of South Australia, from February to October.

Community Collections Power Research

Since July, an increasing number of citizen science volunteers who’ve been recording the fish mortalities on beaches, have also collected and frozen target fishes, as part of a collaboration between community and researchers.

The project links university, government and independent scientists with community specimen collectors, and provides an unprecedented opportunity to obtain many fresh fish samples for research projects. Some of the numerous ways in which the ‘morts’ are being utilised include reading the otoliths (‘earbones’) to determine ages of the fish; creating age-length keys for longer-lived, previously little-studied reef fishes; reconstructing life history using analysis of elements; reproductive studies, and genetics. It is possible that a new species of shallow-water anglerfish (frogfish) may be described for South Australia, following genetic study of the specimens.

Community-Led Rehabilitation of HAB-Affected Fishes

On southern Yorke Peninsula, local resident Phil Bamford began rescuing HAB-affected small fishes that were beached in the incoming night tides over August, and rehabilitating them in home aquaria. This included a small, live-bearing fish species - the endemic Spotted Snakeblenny Ophiclinops pardalis, known to date only from South Australia. A related species - Eel Snakeblenny (Eelblenny) Peronedys anguillaris - also washed up.

Endemic spotted snakeblenny - rescued from the HAB - Phil BamfordSnakeblennies live on the sea floor in seagrass leaf litter, near the base / roots of seagrasses. The rescued fish from waters where harmful Karenia was active, soon acclimated to the cleaner seawater in the tanks, and breathing and movement improved rapidly. The fish started eating, swimming, burrowing and displaying other normal behaviours within three days of rehab. One of the two snake-blennies even gave birth to live young.

Over spring, the project has expanded to include several tanks, regular water quality testing, growth of live brine shrimp and flea mussel food sources, and addition of rocks and cleaned live seagrasses from beach wash-ups, to provide suitable habitat for the benthic fishes.

the vision

It is hoped that with time and support, the project can grow to become a larger scale aquarium-based facility for Yorke Peninsula, for:

post-HAB habitat restoration research trials in conjunction with restoration experts from universities and community orgs (e.g. for marine vegetation, razorfish, mussels)

larger-scale holding tanks, for growing seagrass and canopy seaweeds to be planted out on Yorke Peninsula when once established

fish breeding and re-stocking studies and trials,

marine education / hand-on training and excursions and primary and secondary level.

Tracking Recovery

As the bloom concentrations have eventually weakened in some regional coastal areas, and the water has started to clear, the long process of assessing subtidal impact and recovery has expanded, will continue into the coming years and decades.

At Edithburgh and Wool Bay, the community-based Marine Watch projects are undertaking a variety of monitoring activities. Examples include quadrat-based benthic imagery, and photogrammetry to systematically monitor selected jetty piles at Wool Bay.

The method enables citizen scientists and research mentors to track structural and biological changes over time with high spatial accuracy. Divers are also monitoring the regrowth and change over time in species composition of canopy and understorey seaweeds, and the recovery of the species composition and relative abundance of fishes and macro-invertebrates. Divers regularly photograph and video their observations, and record on iNaturalist.

Learn more about Edithburgh and Wool Bay Jetties Marine Watch

Photogrammetry monitoring image by Edithburgh and Wool Bay Jetties Marine WatchOn NE Kangaroo Island, Bay of Shoals was hard hit by Karenia over autumn and winter, with mass deaths of fiddler rays, razorfish clams, worm eels, rock crabs and many other species. In spring, citizen science volunteers have marked out areas where eelgrass beds were damaged during the HAB in autumn. Percentage cover (density), and percentage live seagrass per area are being monitored over time, in an area where many Pinna dolobrata Razorfish were also killed by the HAB. North-eastern Kangaroo Island may also be a site for razorfish restoration trials in future.

Tracking Seagrass Recovery at Bay of Shoals

Seagrass monitoring site, by Kathryn LewisMussel Restoration Trials underway

Further south in Encounter Bay, local Victor Harbor residents, Ozfish volunteers and staff are investigating intertidal mussel restoration trials. These important structural habitats serve many environmental functions. Mussels help to reduce erosion of the coastal sea floor, and form a hard structure that encourages settlement of other invertebrate species. Mussels remove microalgae & sediment, nutrients, harmful bacteria & heavy metals in coastal waters. They provide surface habitat for other animals, and protection from heat, dehydration, and predators. Mussels are also a food source for some fishes, crabs and shore birds.

Some of the hundreds of dead mussels observed at Kingscote by Janine Warren (left) and pointing to live mussels in Encounter Bay by Samantha Sea. (right) The first step is documenting the live mussel patches that can be used as ‘sources’ to seed biodegradable coconut fibre mats with mussels, and monitor mussel settlement, growth, and spread over time. If the trials are successful, this low-cost, community-connected restoration method may be suitable for other parts of South Australia – such as SW Yorke Peninsula and NE Kangaroo Island - where mussel beds have been degraded by the HAB.

Janine Baker is a marine ecologist and educator with 35 years of experience in South Australian marine research. She is an expert in species identification and biodiversity of the Great Southern Reef, contributing significantly to marine conservation efforts.

Read the comprehensive previous update by Janine for a deep dive into the marine crisis. She tracks the bloom’s persistence into autumn, the staggering loss of marine life and habitat, the patterns in species mortality, and the evidence pointing to widespread ecosystem collapse

Read Janine’s initial analysis of the harmful algal bloom. In this article Janine lays out what we know so far: the species involved, where the bloom is spreading, how marine life is being hit, and what data and citizen science are telling us.